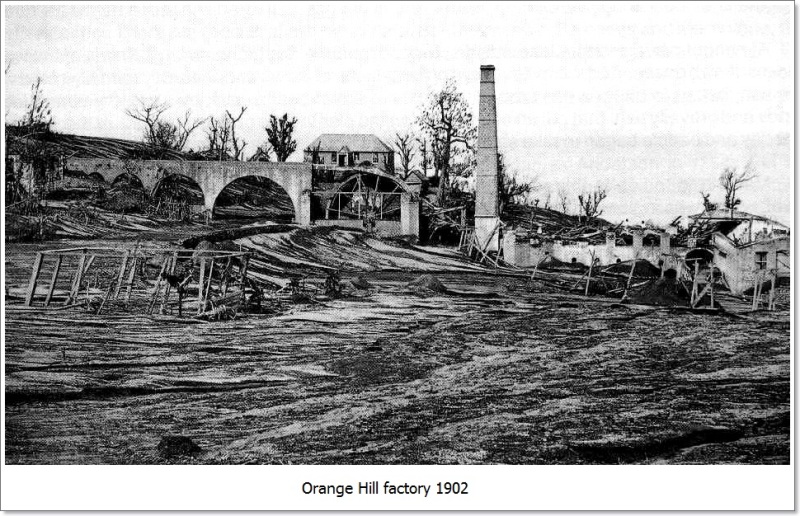

Past events in St Vincent and the Grenadines, have always fascinated me, none more so than the Soufriere volcano and the 1902 eruption. My Great Grandmother, who lived in Georgetown, was about 11 years old when it happened and use to tell us about it but as a child, much of it stayed in my memory. The following events will show that Georgetown, miraculously escaped with no deaths, the reason being that the deadly black clouds which carried red hot dust and sulpherrous gases did not pass over Georgetown.

The information below is adapted from a written account by Tempest Anderson and John S Feltt. First published in 1902. In this account the sequence of events of the eruptions of May, 1902, relied principally on the evidence collected from the statements of eye- witnesses, and on written accounts of the eruption given by residents in St. Vincent.

A strong feeling that something was going to happen

For 90 years the Soufriere had slumbered, and few were living who had seen it in eruption. But in the early part of 1901 an uneasy feeling began to arise in the minds of those who lived on the flanks of the mountain. Earthquakes are by no means infrequent in St. Vincent, though usually of slight severity, but in February and March, 1901, they became so numerous around the north side of the volcano as to awaken suspicion that danger was threatening.

There are two settlements of Caribs, the remains of the original inhabitants of the island, at Morne Ronde on the west and at Sandy Bay on the north east of the mountain. The Caribs are certainly not deficient in courage, but they became so apprehensive that they petitioned to have their settlements removed to some other part of the island, and officials had to be sent to quiet their fears.

These early earthquakes were accompanied by rumblings, which appeared to come from the interior of the hill. Apparently they did no damage to buildings or other structures, but so much alarmed were some of the black labourers that the managers and owners of estates had, in some cases, to take steps to ease their apprehension and encourage them to continue working in the district.

Earthquakes and noises continued through the whole of the ensuing twelve months. The white inhabitants regarded them with indifference or curiosity, for as earthquakes are by no means rare in St. Vincent, the repeated small shocks felt during 1901 were not regarded as a threat. There were some, however who aware of the suddenness with which the eruption of 1812 had broken out, could not help suspecting that there might be another outburst.

In the latter half of April, 1902, they increased considerably in number and intensity. At Owia, on the 13th of April, at 12.20 pm, there was a sharp shock, and about that time as many as eight tremors were sometimes experienced there in 24 hours, all slight and of short duration. Along the whole north-west quadrant of the hill the violence of the earthquakes in the last week of April, 1902, was exceptional. They dislodged stones from the cliffs of lava and sent them tumbling down the slopes, damaging the crops which were planted there.

As yet the Soufriere had shown no symptoms of actual eruption. The Caribs at Morne Ronde, however fully anticipating an outburst, were preparing to evacuate their houses and flee to Chateaubelair and other places of safety. By 1.00 o'clock on the afternoon of Tuesday the 6th May, there could no longer be any doubt that the Soufriere was in eruption.

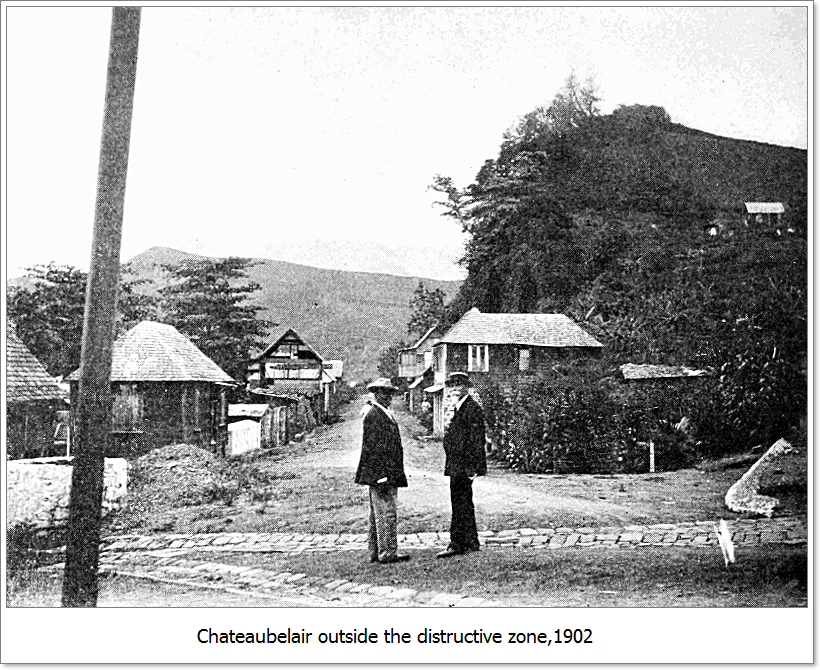

Chateaubelair

On that morning they were flocking into Chateaubelair, and a general anxiety was awakened in the neighbourhood. The day was very clear, and the whole lip of the crater could be perfectly made out by those on the south-west side of the hill. From the north side, the crater is concealed by the intervening Somma wall, while the inhabitants of the windward quarter could see none of the upper parts of the mountain owing to the thick trade wind cloud which covered them.

Between 11am, and 12 noon the labourers on Richmond Estate noticed puffs of steam arising from the crater and reported the fact to the manager. This seems to be the first trustworthy observation of activity on the part of the volcano. Word of this was not long in spreading to the adjoining estates. At 1.30pm, steam was seen by an observer at Wallibou ascending in a great pillar which spread out like a palm tree. It rose from the centre of the old crater.

Then at 2.40 pm, there was a loud report like that of cannon and a great cloud of white steam shot up into the air to an immense height. Word was at once sent to Kingstown, by the officer in charge of the police station at Chateaubelair, and the news that the Soufriere was in eruption was soon flashing over the island.

In a very short time Chateaubelair was full with Caribs from Morne Ronde on their way back to Rosebank, a little further south, where there was another Carib settlement. "Some had passed through earlier in the afternoon, and their fears had been mocked at by those whom they met." By 5 o'clock the village of Morne Ronde was deserted.

As the afternoon advanced matters got distinctly more threatening in appearance. The trade wind cloud hovered as usual over the mountain, but the ridge on the south side of the crater was visible from Chateaubelair.

At 6 o'clock a thick cloud of steam was emitted and from Wallibou, fire was seen forming a ring around the lip of the crater and a crackling sound was heard which sounded like " brush on fire." A stampede ensued in the villages and plantations. The little village was crowded with refugees from the western base of the hill and the whole population was standing in the streets and on the beach watching the progress of the eruption.

At 7.30 pm, a great explosion followed, accompanied by a loud noise and by slight earthquakes. The discharge of vapour was greater than any of those which preceded it. By means of the telephone, constant communication was kept up between the police station at Chateaubelair and the head office in Kingstown. Chateaubelair was becoming more and more crowded with refugees. Captain Calder, the Chief Constable, decided to proceed with an additional force of policemen. Dr. Dunbar Hughes, the district Medical Officer, and Dr. Christian Branch, Medical Officer at Kingstown, accompanied him to Chateaubelair.

Their boat was entering Chateaubelair Bay, just about midnight. The night was calm and clear and on the way north they had passed several boats laden with fugitives fleeing southward. Just as they reached the wharf, a powerful explosion took place. A column of steam ascended rather higher than the mountain itself, about 4000 feet. The whole width of the mountain top was outlined with leaping flames, red and having the same appearance as a cane field on fire. The whole top of the mountain burst into flame, the long flashes of deep red fire traveling from the top downward in a circular track. This was immediately followed by an explosion as of much heavy ordnance, dying away in a long drawn angry grumble. They found the black population madly excited, and standing gazing on the mountain.

Georgetown had no idea that Soufriere was erupting

Evidence of a party of fish sellers who left Chateaubelair and crossed to Georgetown on the afternoon of Tuesday 6th May.

The party consisted of several black or coloured women and one boy. Fish are obtained only on the Leeward side of the island, as the heavy seas on the windward side render small boats unsafe and these women were accustomed regularly to cross the island and were in consequence very well acquainted with the appearance of the path and of the crater under ordinary conditions.

They left Chateaubelair about 6 o'clock. They had no reason to suspect that an eruption was imminent till they were just below the summit, when they heard rumbling noises and felt the hill shaking. The smell of sulphur from the lake was much stronger than usual and on looking down into the crater they saw that the water was much discoloured, in places red in other places milky, but elsewhere bluish-green, as usual.

Another woman traveling by the same path, but in the opposite direction, passed the crater about mid-day. As she was descending on the Leeward side and was near the " half-way tree' a well-known landmark, she heard a loud report, and saw a rush of steam, where upon she dropped her basket and ran. This must have been the explosion which took place about 12.30 pm. She saw no stones on the path either when ascending or descending.

Another woman traveling by the same path, but in the opposite direction, passed the crater about mid-day. As she was descending on the Leeward side and was near the " half-way tree' a well-known landmark, she heard a loud report, and saw a rush of steam, where upon she dropped her basket and ran. This must have been the explosion which took place about 12.30 pm. She saw no stones on the path either when ascending or descending.

By Tuesday evening everyone in Chateaubelair and on the Leeward side of the mountain was well aware that the Soufriere was in eruption. Boats had left Wallibou in the afternoon and gone up along the coast as far as De Volet and Campobello, carrying the news. Windsor Forest Estate was vacated on Tuesday night, and it was only the scarcity of boats which prevented all the inhabitants north of Chateaubelair from fleeing to the villages in the south.

At Fancy and Owia, no trustworthy information of impending danger had yet been obtained. The crater cannot be seen from this side, and the mountain was capped with cloud. People were somewhat anxious on account of the frequency of earthquakes during the previous weeks, and also because word had reached St. Vincent that Mt Pelee, in Martinique, was in a state of activity. But so far nothing had been seen or heard which indicated that an eruption of the Soufriere was actually in progress.

On the windward side, in Georgetown and the estates on the Carib Country, there was almost as little apprehension. Telephonic messages had been sent from Kingstown to police headquarters at Georgetown, that the people at Chateaubelair had seen steam arising from the crater. But a dense trade-wind cloud covered the mountain, the rumbling sounds were mistaken for thunder, and in the West Indies there is always so much untrustworthy news in circulation that it is not difficult to understand that this unexpected information was received with scepticism.

The afternoon of Wednesday May 7th.

On Wednesday morning, day dawned on a scene of great excitement in Chateaubelair. The usually quiet village resembled a hive of angry bees. Just about 6.00 am, (at sunrise) there was a large outburst of steam, and as the afternoon wore on the violence of the activity increased. Work was at a standstill, the magnificence of the eruption absorbed all attention. The last stragglers were coming in from the estates and villages on the Leeward side, where few had been brave enough to remain overnight and most of these before midday, were convinced that it was advisable to take to flight. No further observation was noted at Richmond Vale House till shortly after 6.00 am on the 7th, when a discharge took place with the usual column of thick vapour, but beneath this was a much shorter column of almost dense black, and of a heavier nature, as it quickly subsided back into the crater.

At this time there was thunder and lightning, showers of black and heavy material could now be seen thrown outwards and felling downwards from the column of whitish vapour, associated with loud noises and more violent outbursts. The eruption was now assuming an acute phase and the explosions followed one another with increasing rapidity and violence. At first, the steam clouds emitted from the crater followed one another at intervals of an hour or less and between the outbursts the crater could be seen gently steaming, but about 10.30 am, they had so increased in number that an enormous column of vapour was rising from the throat of the volcano and spreading out in a great mushroom-shaped cloud above the summit of the mountain.

On Wednesday morning the fish sellers who had crossed to Georgetown on Tuesday, started at day-break to return. Nothing had been seen on the windward side to make them suspect what was going on at the crater. As they went up the path, however, near the " River Bed " (about a mile above Lot 14), they noticed where stones had fallen and indented the earth. This was probably between 8 and 9 o'clock. They pushed on to near the summit of the hill, though they heard noises and saw cracks in the earth, for they little knew the dangers they were facing.

The top of the mountain was covered with mist and most of them followed the path up to the base of the summit cone. Some went up to quite near the lip of the crater or possibly even to the actual edge. What they saw there was enough to dismay the stoutest hearts. They turned and fled back along the path, and meeting others ascending, told them what they had seen and all returned together. As they passed the estates by the roadside they spread the news that the Soufriere was in eruption, and the lake had boiled over. They were received with incredulity, and when they came to Georgetown they were scoffed at as fools and cowards.

The fish sellers who crossed the island on Tuesday morning had reported that the crater lake was boiling, and through the night rumbling noises had been heard and earth-tremors felt in several places. The black labourers, among whom evil tidings spread with a marvelous rapidity, were far from confident, and though sugar making was started as usual on several estates, and there was no cessation of work anywhere, it was thought advisable by some of the managers to send a party of white men up the mountain to see what was really happening there.

This appears to have been determined on after the receipt of a message from Mr. Pouter, the proprietor of most of the estates in this quarter, that the Leeward side had been evacuated, and great anxiety was felt in Chateaubelair. The party started from Turema and Orange Hill, and rode up the path to the back of Lot 14. There they met the fish sellers returning from the summit after their ineffectual attempt to cross to the leeward country. This must have been about 11 o'clock, and fine ash was now falling around the lower slopes of the hill, so partly for this reason, and partly from the information given by the fish sellers, they returned to Orange Hill, and reported that it was only too true that the Soufriere, after its long quiescence, was once more going to erupt.

THE ERUPTION

About 11 o'clock rain began to fall containing particles of ash, and the noises from the mountain became louder, more frequent, and more threatening. On some of the estates, work was then stopped, and many of the labourers took flight to Georgetown. Others continued to work till near 1 o'clock, when there was a sharp fall of gravelly stones, this put an end to all sugar-making, and people fled to their houses, or began to hide in the cellars, or the rooms of the larger residences in which the managers lived.

Smoke could now be seen ascending in vast columns from the crater. Many tried to escape to Georgetown, but when they got to Rabaca they found the Dry River there pouring down in high flood, and the water was so hot it was impossible to get across. There is no bridge over this river, so most of these refugees gathered at Rabaca House, but some returned to their own dwellings.

Smoke could now be seen ascending in vast columns from the crater. Many tried to escape to Georgetown, but when they got to Rabaca they found the Dry River there pouring down in high flood, and the water was so hot it was impossible to get across. There is no bridge over this river, so most of these refugees gathered at Rabaca House, but some returned to their own dwellings.

Previous to 7th May, there were signs noticed in some places that the crater was in action, but at Georgetown there was no sign observed till the very day, in fact, one can almost say the very hour. On the morning of the 7th, reports of the Soufriere's activity were being questioned for the simple reason above stated. When women and children went to perform their various regular duties everything appeared as usual.

Report from Georgetown School

In Georgetown it was not till about 11.00 am that it became known with certainty that a catastrophe was impending. Mr. J. W. Clarke, teacher in the Government school, gave an account of his experiences that morning. "I kept my regular 7 to 9 private school. Shortly after 9:00 am., sounds resembling distant thunder were heard, but it was not until 10.15 am when particular notice was taken of the sounds, from their long-continued detonation. I was engaged marking my school register of attendances from 10.15 to 10.30 am, during which time the noise increased. At about 10.40 there was a distinct flash of lightning seen from the direction of the mountain, followed by a crackling peal of thunder."

"At 10.45 I got a little uneasy, and just at the same moment I got a message from Mrs. Ballantyne, asking me to send home her daughter, who was then at school. I hesitated for a few minutes, and when in consideration of what should be done, another stroke of lightning followed by heavy thunder was seen. I then complied with the request, and feeling apprehensive of danger, I at once went to the manager of the school, Mr. H. B. Isaacs, and suggested that the school should be dismissed, and the children sent home till matters cleared up, after a few minutes consideration, the suggestion was granted and I hurried back and in a few words, dismissed the school."

"It was now about 11:00 am, and the rumbling noise still continued. About 11.15 am drops of water containing sulphurous matter fell, and that was the first direct sign which told me of the disturbance of the Soufriere. The water continued falling only in drops here and there. At this stage, very minute particles of dust or ashes fell, but were only observable on white material. My boots at this time were besmeared with the sulphurous matter mentioned, as I kept walking from one place to another. At about 12 noon I was standing under the galvanised roof of the Grey's store when small pebbles, about a pea grain size, commenced to fall.

It was about 1.30 pm, when smoke was distinctly seen issuing from the crater, and volume after volume rose, only to ascend higher than the former. The clouds of smoke got blacker and thicker and each mass seemed to travel faster than the first. At about 2:00 pm, pebbles of a larger size commenced falling, and it was becoming injudicious to move about.

The People of Georgetown only had 3 hours warning before the eruption.

One of the most remarkable features of this eruption is the suddenness with which it broke out. At Chateaubelair steam was seen ascending from the crater on Tuesday morning, and the inhabitants had at least 24 hours notice before the volcanic activity assumed a dangerous phase about noon of Wednesday. But everywhere else around the mountain there was no certainty till about 11 o'clock on Wednesday morning or only 3 hours before the climax was reached, and the great black cloud swept from the crater to the sea, burning and suffocating those in its path. Had the Leeward side of the hill not been clear of mist, so that a view of the crater was obtained by those dwelling there, the loss of life would certainly have been much greater than it was, for the noises would have been mistaken for thunder, as they were at Georgetown.

The Climax of the Eruption. "The Descent of the Great Black Cloud."

The climax of the eruption was now at hand. It came with terrible suddenness. With laconic brevity, Mr. McDonald records it as follows. " 1.55 pm, Bumbling large black outburst with showers of stones all to Windward, and enormously increased activity over the whole area. A terrific huge reddish and purplish curtain advancing up to and over Richmond Estate.

The lightning and thunder at this time were terrific, and there were noises inland. Everything seemed to point to a general break up, both on land and sea. This was the outburst of the great black cloud, which charged with immense quantities of red-hot dust, poured from the crater and swept down the valleys to the sea. The cloud swept out to sea over Richmond, its southern margin was over the headland on the south side of the mouth of the Richmond River. Richmond Vale House stands in the next valley to the south of Richmond Estate, and it was spared but little damaged, while Richmond was wiped out and destroyed.

It is interesting to compare with Mr McDonald's description with statements made by some black and coloured men, who were just a little further north than Mr. McDonald, and were caught in the edge of the cloud.

They had been at Richmond to remove their personal belongings to Chateaubelair, and their boat was returning when the black cloud swooped down. The sea was perfectly calm and the day clear, though there had been a few drops of rain in the morning. The boat had just rounded the point south of Richmond River and was on the north side of Chateaubelair Bay. The cloud struck them like a strong breeze, though being under the shelter of a high spur of land, they did not feel it much. Still it came over the water with a strong ripple and a hissing sound, due to the hot sand falling into the sea and making it steam. In a moment it was pitch dark and intensely hot and stifling.

The cloud was highly sulphurous, and this irritated their throats and nostrils, making them cough. The heat was terrible and the suffocating feeling very painful. They threw themselves into the sea to escape burning by the hot sand. They all dived, and when they returned to the surface the air was still unfit to breathe and the heat intense. So they continued to dive repeatedly, but when they came up again the air was almost as bad as before. How long this lasted they cannot tell, but they thought it might have been several minutes. At last they were all utterly exhausted and could have held out no longer, then they felt the air clearing, the heat diminished, though still very great, and they clung to the boat for a few minutes before they were able to get into it again.

One man was not so good a swimmer as the others, and his strength was soon exhausted. He held on to the gunwale of the boat and took the risk of burning rather than of drowning. He described the insufferable heat and the sulphurous smell, and he was rapidly becoming unconscious when the air cleared. The sea around was hissing, and it was so dark that two men hanging on to the boat, side by side, could not see one another, even though they could touch.

When the cloud had passed there was enough sand on his scalp to fill his hat twice. The ash fell dry, there was no rain and no scalding mud. When they got back into the boat they found it nearly filled with fine ash and stones, and these were so hot that had the boat not been leaky and partly filled with water it might have taken fire. Yet these men were only in the outer edge of the cloud. A few hundred yards further north this cloud deposited in some places 40 feet of red- hot sand in a few minutes. It was for this reason also that they experienced no great shock when the cloud struck them, and did not feel it pass like a strong blast. Another man, who was caught in this cloud and survived, gave a very interesting narrative.

He was coming south from Campobello on the north shore in a boat with several others. That morning he had gone north from Morne Ronde to rescue his family, and when he got to Campobello the people there knew nothing of the eruption. His party left at 1 o'clock, and a little later they passed Windsor Forest. This was a grazing estate, and he saw that all the cattle were gathered on the beach, running to and fro and bellowing with terror. A few minutes later he heard the sound of a great explosion and saw a huge black mass pouring out of the Wallibou and Larikai Valleys to the south of him. Terrified, he started to return, but at Baleine another similar cloud was rushing down the ravines on the mountain side to the north. No course remained open except to stand right out to sea.

Small stones began to fall in the boat. Then he was enveloped in dense darkness and ash fell, at first wet but afterwards dry and quite cold. By this time they were several miles out from the shore. Another boat was quite near him when the darkness descended. It was never seen again. He thinks it was filled with sand and sunk, for the downpour of ash and stones was so heavy that they had to keep constantly bailing it out. He rowed right out to sea, and that night the tide took him to quite near St. Lucia. When it turned, it carried him back again, and next morning he landed near Chateaubelair.

The Windward Side

On the windward side of the island the black cloud descended in probably no less volume than to Leeward. In the Carib country work in the fields had stopped, and in the sugar works, though they were full of people, no sugar making was going on. Everyone was watching the progress of the eruption in mingled fear and admiration. Small stones began to fall after mid-day, and about half past one in some places there were showers of hot scalding mud.

The cattle, horses and mules were mostly out grazing, but nearly all the people had gathered into the more substantial buildings, the managers houses or the stores and cellars attached to the sugar works, though many were in their huts in the villages adjoining the estates. Some had been struck with falling stones, but as yet probably no one was killed, and but few injured. Then, with a loud roar, at 2 o'clock the great convulsion came. Those who were in the open air saw the huge black cloud rolling down the mountain in globular, surging masses. They fled into the houses and shut the doors. Onward it rushed with a loud rumbling noise and filled with lightning. Anyone who were in the open air perished at once. Many of the negroes huts were so densely crowded with people, that there was hardly standing room.

At Lot 14, the manager and his wife and family had shut themselves up in the rum cellar below the house, and firmly closed all doors and windows. They had a terrible experience, but they survived. All of those in the house itself or in the negro village were killed. It will be understood that as the tropical houses are so built as to secure free entrance of air, it is almost impossible to close them up securely, and the suffocating blast reached the interior and stifled all who were there. All the animals in the fields also perished.

At Lot 14, the manager and his wife and family had shut themselves up in the rum cellar below the house, and firmly closed all doors and windows. They had a terrible experience, but they survived. All of those in the house itself or in the negro village were killed. It will be understood that as the tropical houses are so built as to secure free entrance of air, it is almost impossible to close them up securely, and the suffocating blast reached the interior and stifled all who were there. All the animals in the fields also perished.

At Rabacca, many who were prevented from fleeing to Georgetown by the floods of hot water in the river had gathered in the manager's house. In one large room there were fifty people. When they saw the dark cloud coming, they firmly shut all the windows fortunately they were substantial and well-glazed and everyone in this room was saved. They felt the heat most intense. It was quite dry, and there was a very strong and irritating odour of sulphur. Some fainted, but all survived.

The overseer said that from the window he saw the black cloud rolling on towards them, when it reached the house there was darkness, and a sharp fall of stones on the roof. The cloud rolled down upon the sea below the house, and when it struck the water it was " filled with fire." It seemed then to rebound from the surface of the sea and return towards the building, and at this time the wall of a ruined sugar store was knocked down, probably by lightning, as nothing else was overturned. It was when the cloud returned from the sea that the suffocating feeling was experienced. Practically all who were in the negroes huts or in the open air perished.

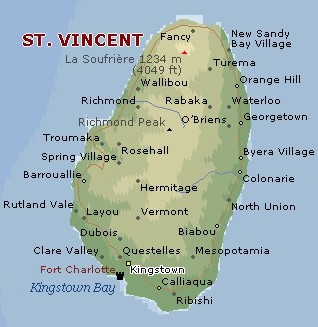

At Orange Hill, there was a large substantial stone built rum cellar, which by the orders of the manager, was left open to afford a refuge for any who wished to avail themselves of it. About seventy crowded together there. The windows were not shut, but they were small and faced the sea, so that the blast did not directly strike them. One man stood by the door holding it ajar to admit any who fled from the huts in the village. Forty were in the cellar, and all were saved. Thirty were in the passage leading into the cellar, and they were all killed. None of those survived who remained in the labourers huts, or were fleeing to and fro about the yard in abject terror. Many shut themselves up in a store with a galvanized iron roof. All died, and were found buried in sand with the roof collapsed and fallen upon them.

At Turema (Tourama) the fatal cloud did its deadly work quite as effectively. All who were in the manager's house, estimated to number thirty five, were killed. One woman survived for three days, and was found by the first search parties who went out from Georgetown. She begged for water to drink, they gave her some, and returned to make arrangements to have her taken to the relief hospital, where she died shortly after her arrival. In the Great House or Mansion House, four were killed in the kitchen, where the windows and doors had not been effectively closed. Two shut themselves up in another room, closing all apertures as thoroughly as possible, and they survived. All who were in the villages or fields perished, without exception. click here to see the Orange Hill viaduct as it is now.

In Overland village the loss of life was terrible, hundreds were killed. In one small shop by the roadside, in a room perhaps 15 feet square, eighty-seven bodies were found. One man who was interviewed had lived in this village, in his house seven died, but four or five survived. When they saw the black cloud coming down, they shut up all doors and windows as tightly as possible. As the hot cloud approached, it was red at first, but changed into black before it passed overhead, the heat was dreadful, and the lightning very vivid. The air smelt very strongly of sulphur, and their throats were dry and parched. Some burst into spasmodic coughing from the irritant sulphurous acid and fine dust in the air. Many cried out for water, but in a few seconds the suffocating feeling prevented articulation. Then several threw up their hands and fell dead. Others collapsed, but lingered in some cases for an hour or more.

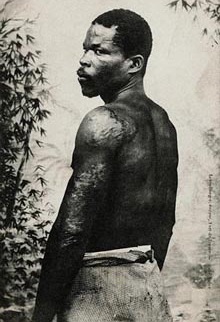

Those who survived state that in a few seconds it would have been all over with them. But the air began to clear, there was a slight breeze off the sea, and the windows on that side were thrown open and with a sense of great thankfulness, they inhaled again deep breaths of cold pure air. Here, as at Rabacca, those who were watching the cloud state that as it struck the surface of the sea it flashed with fire. One man showed where the back of his fore arms had been severely burned by hot mud or ash which came down with the black cloud. The parts of his body covered by clothes were protected, but his shirt sleeves were rolled up, and his arms below the elbows were bare.

The Fancy estate lies almost due north of the crater, and about 3 miles distant from it. It is actually nearer the focus of eruption than either Wallibou or Lot 14, though those two have suffered much greater damage. Mr. Cubbin, who was the local teacher, supplied some interesting notes regarding the events of that afternoon.

About 2 o'clock there was a fall of stones, which increased in severity till the manager, Mr. Beach, considered it desirable to collect all the people on the estate in a large iron-roofed main building. Dark clouds were then seen pouring out over the sea on each side, and soon they broadened till only a narrow passage was visible between them to the north. The mass of falling debris seemed to be closing in upon us, and in a short time it fell, enveloping the building and almost suffocating the inmates, during this time there was almost total darkness. In a few minutes there was a glimmering light, as at dusk.

The houses in the village, or most of them, were now observed to have been demolished, this was caused by the falling debris and by lightning, and most of the people who remained in the village were either dead or fearfully burnt. Many of them died by next morning, The estates building was of stone with galvanised iron roof. The windows were all closed, but the door was open at the time the cloud descended, and was shut by the force of the blast. All who were in the building were saved, but about forty were killed in the village. Those who escaped were badly burnt, mostly on the hands, the feet, and the face, but others also on the parts protected by clothes, though their clothing was not scorched or ignited. The dust in the cloud was not red-hot, and consequently did not set anything on fire, the burns being apparently due to steam and other gases. Much of the damage done on the Fancy estate was apparently due to lightning.

We were told by one man, who was looking out of the window of the rum cellar at Orange Hill, that he saw a woman starting to run across the yard to the building from one of the huts. That instant there was a bright flash, and she fell dead. The corpses of some of the animals which perished in the fields gave evidence of having been struck by lightning, and everywhere on the devastated estates it is easy to find trees which show the effects of the same agency.

At Owia, according to Mr. Effingham Dunn, small and large pebbles were falling about 1 o'clock, and from 1.30 to 1.45pm, there was a rain of hot liquid mud. At this time there was a nauseating odour of sulphur, but it only lasted about half an hour. It now became very dark, and from about 2 o'clock to 3 o'clock the heat was almost suffocating, and I had to throw water about the house to make breathing possible. At Owia the damage done was comparatively slight. The crops were injured but not buried, and none of the inhabitants were killed.

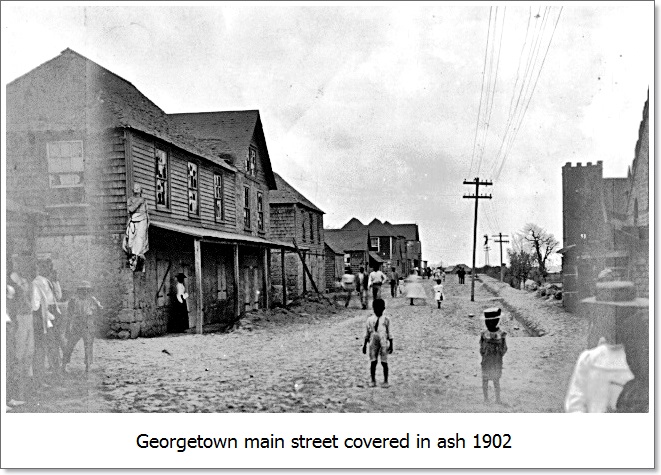

At Georgetown, no lives were lost, and it seems certain that the deadly black cloud did not pass over the town. A little after 2 o'clock the inhabitants heard a very loud sound proceeding from the crater. This was described to us as " a long, loud, mournful, unearthly, death-like roar." The mountain at that time was emitting an enormous column of steam, which expanded and spread out laterally as it ascended in the air, and red-hot stones were tumbling down the slopes, giving out trails of sparks. A heavy fall of scoria and stones followed the outburst. Darkness then set in fairly rapidly, though by no means instantaneously, and the rain of ash began. It continued through the whole evening and the early part of the ensuing night.

The first estate north of Georgetown is Mount Bentinck, and here also no lives were lost, though the fields were buried in ashes.

Langley Park, stands half-a-mile to the north of Mount Bentinck, and many were killed there. In the main building some thirty or forty bodies were found. It is clear that the black cloud passed over Langley Park, and that the fatalities which took place there are to be ascribed to its action. Mount Bentinck and Georgetown escaped, and this shows how sharply defined was the lateral margin of that mass of deadly vapours and dust. It shows also how harmless was the rain of ashes from above, as no one was killed south of the limits of the cloud, though a few were injured by falling stones.

"Many tried to escape to Georgetown, but when they got to Rabacca they found the Dry River there pouring down in high flood, and the water was so hot it was impossible to wade across. There is no bridge over this river, so most of these refugees gathered at Rabacca House, but some returned to their own dwellings."

The Rain of Ashes.

The history of the later stages of the eruption which followed the descent of the great black cloud cannot be given with the same fullness and detail as that of the earlier phases. Darkness now covered the mountain and much of the surrounding country and little could be seen except the flashes of lightning and the occasional fall of red-hot stones. The inhabitants had shut themselves up in their houses, and many were engaged in helping the wounded and dying, so far as that was possible. Others had hid themselves in inner rooms and cellars in momentary expectation of a sudden and painful death. No man was sure of his life for a moment.

Everyone believed that most of his neighbours and friends had perished. Many dreaded that the sea would invade the land in great tidal waves. The earth rocked and shook continuously, and those who dwelt in the more substantial stone-houses were afraid that they would fall on them. The air and sky were filled with lightning which quivered and played incessantly. Many houses were already on fire, and trees and buildings were frequently struck.

Fine ash were raining down upon the roofs of the houses, which were rattling under this bombardment. Every now and then a fall of bigger stones would crash with a loud noise on the wooden or iron roofs, and not infrequently these were perforated by large stones which landed in the rooms among the frightened survivors. Those who ventured out protected their heads with pillows or pieces of wood, or even with tubs.

The ground was covered with a layer of ashes which, though, warm could without difficulty be walked upon. The air was charged with fine falling dust, which irritated the nasal passages, giving rise to coughing and sneezing. A few remarked that immediately after the great outburst which took place about 2 o'clock in the afternoon, the pressure of the air seemed to be increased and the effect from the sound of the roaring mountain was at times acutely painful.

For about two and a half hours in the afternoon the noise was terrible, Even at Kingstown it was so loud that it resembled no sound with which the observers were familiar. Some compared it to the discharge of an enormous gun, except that it was continuous and not intermittent, and we were reminded that among the Caribs there were old traditions regarding the " Great Gun of the Soufriere. Most people described it, however, as having a long, drawn-out, weird, unearthly character, recalling the roar of a wounded animal in intense pain.

The air also was laden with sulphurous fumes. Especially noticeable during the passage overhead of the great black cloud, when the abundance of sulphurous acid was so great as to produce an intense feeling of irritation and suffocation. The intense heat, however, was even more oppressive than the sulphurous vapours, Within the precincts of the dark cloud it was terrible. The sufferers cried for water, till the scorching of their throats prevented articulation, and they fell groaning to the ground.

When the great black cloud was seen rushing out to sea past Chateaubelair, even those whom courage, or a sense of duty, or helplessness, had led to linger in the village, were struck with one impulse to escape. There are some graphic narratives of that night, which give us a picture of the demoralisation of the black population and the terrors of the eruption, so vivid as to be worth reproducing here.

Dr. Dunbar Hughes and Captain Calder, who had both gone there by order of the Administrator, were the last to leave, and Captain Calder's account of his escape is as follows: When the black people realised their danger most of them grew madly excited, and in a few minutes everything in the shape of a boat or canoe pushed off from the shore, weighted down to a dangerous degree with human freight, each one excitedly urging on the others. I could then have left with the police in our boat, but with three or four hundred refugees on the shore I quickly determined that our duty was to remain.

While I was speaking to the people in the street, the excitement and danger were increased by hot, half-melted stones falling from the enveloping cloud. I ordered everyone in the streets to leave the town at once, and to prevent injury by falling stones, I directed them to take old boards and shingles from the dilapidated houses and cover their heads.

Stones up to half a pound in weight were now falling, while the sulphurous fumes and fine light dust rendered breathing difficult. So, with at least three hundred refugees in front, we started out of the Chateaubelair valley, accompanied by the prayers of some and the feeling of despair of nearly all. Men, women, and children of all ages scurried up the steep hill as fast as possible, mothers urging on their young children hardly able to crawl, old men imploring the assistance of the younger and stronger, each helping and encouraging the other, clearly showing the brotherhood a common danger engenders. One poor woman, with a brood of at least eight, was kept behind by the inability of the youngest two to keep up the pace. Her agonised cry for help I can never forget, nor the thankful smile I got when I picked them up, one in each arm.

By this time the dense volume of sulphurous cloud, which chased us like a death pall, began to overtake us, and it was hard indeed to get the people to continue struggling on. As the darkness settled over us, a storm of lightning and thunder broke over our heads, and so near were the flashes that one thought that each surely must strike the people on the road, especially as the dry grass on the hill-sides was ignited. It would indeed be difficult to be more uncertain of another minute's life than on that hill-side that dark afternoon. As we gained the summit of the next mountain, the poisonous dusty cloud was held in check by a steady breeze coming in the opposite direction, but for which the death-roll by suffocation must have been appalling. I pushed on for 9 miles, until I got an opportunity of communicating with Kingstown, when I learned that sulphurous dust and ashes, accompanied by semi-fused stone, had fallen there.

When about 4 miles from Chateaubelair, thinking the clanger from falling stones had passed, I removed the board I had tied over my head, and, as a result, I was struck down, and remained in a semi-conscious state for over half an hour. It is impossible fitly to describe that awful trek through a continual blaze of lightning driven as it were, before that deadly and enveloping cloud of sulphurous dust and ashes. The awful grumbling and rumbling of the volcano continued throughout the night, and as the morning dawned, the deep green of the young arrowroot and cane plants had given place to a smooth leaden colour of dust, several inches deep, not a single green leaf of any description being visible.

The Closing Scenes of the Eruption of May 7th, 1902.

Thursday and the following days, in the north end of St. Vincent the sun rose on scenes of desolation and despair. Three quarter of the population lay dead in their houses, and many of the survivors were fearfully burnt and suffering dreadful agony. The green and fertile Carib country, which had been covered with rich crops, lay buried beneath several feet of hot and smoking ashes. The Soufriere, which on the previous morning had been a mass of verdure and green forest, was now the leaden hue of the new fallen ash. With the return of light, though the air was still misty with falling dust, many fled and sought refuge in Georgetown and the region to the south of it. Others stayed to tend the wounded or to bury their dead. A weary procession of mangled and injured toiled along the road to Georgetown. Already before dawn some had passed through the village fleeing from Rabacca and Langley Park, and they spread the tidings of death and destruction.

Efforts were early made to penetrate the burnt country and help the sufferers. A police-constable went out along the windward coast to ascertain how great the damage had been. The sights he saw were fearful, dead in every village, almost in every house, corpses everywhere along the roadside, dead cattle strewn through the fields, many of the bodies mangled, burnt, and distorted. The injured and terrified survivors, who were unable to make their way along the roads, were lying among the corpses, crying aloud for water to moisten their scorched throats, many had their skin extensively burnt and peeling off their hands and faces. Slate coloured vapours still ascended from the mountain, every noise struck terror into the minds of the survivors.

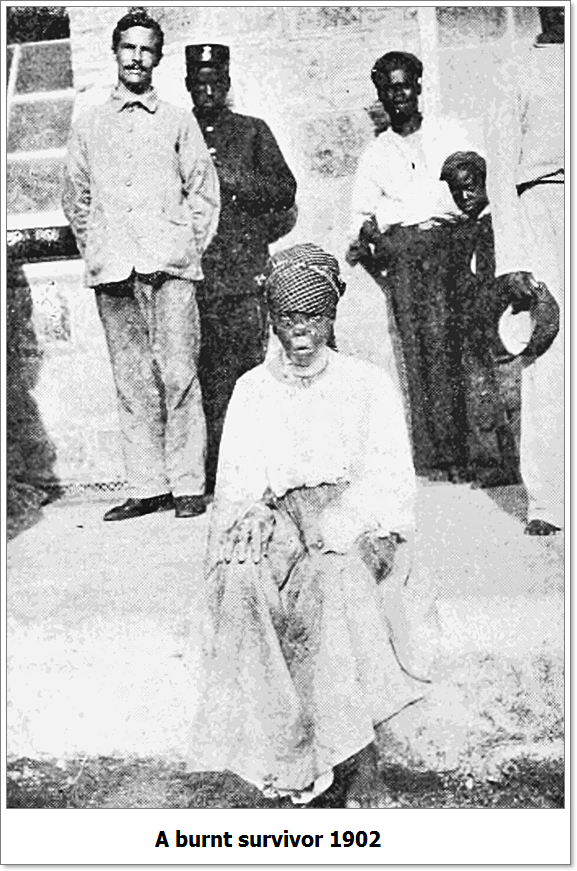

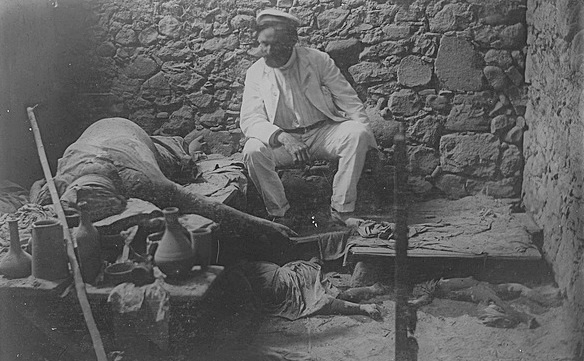

It was difficult to get men to volunteer to explore that thirsty, burnt, and death-struck country. Yet the officials, the clergy, and the inhabitants of Georgetown nerved themselves to the task, and in a very short time the helpless injured were being gathered into Georgetown and accommodated in temporary hospitals there. Pictured right.

The task of burying the dead had to wait. Despairing of assistance, one boy of fourteen buried his father, his mother, and seven brothers and sisters in a trench he dug in the ground outside the house a fact which throws a lurid light on the sweeping nature of the calamity which had overtaken the inhabitants. It was not till some days had elapsed that the work of burying the dead was finished, so many were they and so long did it take to clear the ashes out of the houses, huts, and yards, and bring the bodies to view. The official estimate of the number interred is 1295. It is certainly an under estimate rather than an over-estimate.

The story of the ready response which the British colonies in the West Indies made to the call of assistance and relief is an inspiriting one, but hardly falls to be narrated here. From Trinidad, from Jamaica, Barbados, St. Lucia, in fact from all the British islands of the Caribbean Sea, help was sent. The American Government, without delay, dispatched the "Dixie" with stores and medical comforts.

Lists of subscriptions were opened in England and elsewhere, and money poured in with great rapidity. Nothing was omitted that could be done to save life or mitigate suffering. The efforts of the medical men were crowned with almost no for success, and comparatively few of those who were able to reach the hospitals and place themselves in the hands of the doctors died of their injuries or burns.

Chateaubelair, had been vacated during the afternoon of Wednesday, and its inhabitants were scattered through the villages and houses to the south, but on Thursday morning, as the noises from the mountain had almost ceased, people began to return, as soon as day broke, to see what damage their houses and crops had suffered during the night. From 3 to 5 inches of ashes had fallen in the village, and some of the houses had had their roofs perforated by falling stones. Others had collapsed under the weight of ash that accumulated on them. No buildings, however, had been set on fire, though on the slopes to the south and east of the town in more than one place the grass had been ignited, (probably by flashes of lightning). Most of trees had been stripped of their leaves, and the smaller branches had been broken by the falling stones.

On Saturday, the 10th May, it was apparent that the energy of the eruption was spent and a state of quiescence was at hand. For some time after daybreak the crater was almost free from discharges, but about half past 9 o'clock the steam clouds began to arise again, and continued with intermissions during the remainder of the day. It was obvious to all spectators that the worst was over and that the eruption was drawing to a close. On the 11th, steam still continued to ascend from the crater, and the mountain was veiled in smoke. On the 12th and 1 3th, at irregular intervals, sluggish discharges of salty vapours took place, accompanied by low rumbling noises.

By this time on the windward side of the island considerable progress had been made with the work of interment. The wounded had been relieved and removed to hospital in Georgetown and Kingstown. Most of the population of the districts which lay to the north of the mountain, and which had not suffered so severely as the region to the south, had been drawn away and had settled temporarily in Georgetown, Kingstown, and other parts of the island. At Owia, Sandy Bay, and Fancy there were still green fields to be seen, and though many of the inhabitants fled, some remained.

The Rabacca dry river was dry for several days after the great eruption, and when it began to flow intermittently after very heavy showers the water came down perfectly black and boiling hot. From Chateaubelair several parties made a voyage up along the coast in boats, and some landed to examine the burnt-out plantations of Wallibou and Richmond.

What chiefly attracted attention was the alteration in the configuration of the surface and in the outlines of the coast. The villages of Morne Ronde and Wallibou had disappeared, and the sea had encroached on the land for a width of about 200 yards at the mouth of the Wallibou stream and for a distance of nearly a mile along the coast to the north of this. The buildings of Richmond Plantation and of Wallibou were surrounded by ashes several feet deep. Richmond had been on fire, and all the woodwork of the houses and the furniture was destroyed. Richmond Village which stood below the plantation house, was seen to be covered with 30 or 40 feet of ashes, more or less, and the general level of all the flat land as far as Frazers was raised by 40 or 50 feet.

At this time the Wallibou stream was perfectly dry and choked with sand, which filled it up almost level across. It was not till seven or eight days had elapsed after the eruption that the water was again seen to make its way to the sea.

According to the descriptions given by those who had occasion to visit the devastated country at this time, it was a shadow less wilderness of sand and blasted vegetation, in which not a drop of water could be found to drink. The heat of the tropical sun was reflected from, the bare surface of the sand, making the air intolerably hot, and every breath of wind stirred the fine dust which formed the superficial layer of the deposit, and blew it into eyes, nostrils, and throat. The rains had not yet been sufficient to make the mud coherent or to wash away the finer particles, and the ash lay on the level cane fields with an undulating surface resembling that of blown snow. Rain was urgently needed to restore the blighted trees and enable them to put out fresh leaves.

In Georgetown and Chateaubelair confidence was rapidly restored, and owing to the influx of the refugees, the villages were crowded with people. Rations were now being served out daily to the destitute, and settlements erected for their accommodation, so that there was a bustle of activity, and the streets were thronged. The burial of the dead was over, and the living had had time to count their losses and were congratulating themselves on their escape.

A week had elapsed since the great eruption, there had been no further destruction, though the devastated country was deserted. A few of the inhabitants had been able to return to attend to the interment of their relatives and friends, and to remove the most valued of their personal belongings. As a rule, however, a great aversion to visit the scenes of suffering and death was manifested by the refugees, but they readily adapted themselves to their new surroundings, and when the wounded had recovered from their burns and injuries, they settled down without any great reluctance in the quarters provided for them.

Just when they thought it was all over."Soufriere erupted again on the 18th May, 1902."

The volcano sank into a state of quiescence, after the 15th May no further loud noises were heard, and the emissions of steam were on a very small scale, and took place without violence. The ordinary occupations of life were resumed, and the mountain was no longer observed, hour after hour, with an interest quickened by apprehension. But a rude awakening was at hand.

On the evening of Sunday, May 18th a second eruption took place, less violent and far less destructive than the former one, but still sufficiently vigorous to throw the whole population into a state of terror and make those near the mountain flee for their lives. The afternoon of Sunday was beautifully calm and clear, and the inhabitants of Chateaubelair could see the mountain from base to summit. Many were in boats along the Leeward coast examining the strangely-altered surface of the plantations of Wallibou and Richmond and the startling modifications which had taken place in the coast line to the north of the village. Not a single cloud veiled the face of the mountain and the bare, burnt surface showed up in every detail in the evening light.

Sunset was followed by a clear, starry night with bright moonlight and a cloudless sky. In Chateaubelair, Kingstown, and Georgetown many people were enjoying a walk in the cool refreshing night air, when suddenly about 8.30 pm a loud, prolonged ominous groan burst from the mountain. At the same moment a great cloud of steam shot from the crater and rose to an immense height in the air. As seen from Kingstown, it was pointed and its height was estimated at many thousand feet. In this great mass of vapour, lightning incessantly scintillated. They were tortuous and snaky, and did not resemble the clear flashes often seen on a tropical night.

The noises in Chateaubelair were deafening, many thought they were as loud as on the afternoon of the 7th May. Soon the village was enveloped in total darkness. The inhabitants sprang out of their houses, and seizing their children, fled along the road that leads southwards past Petit Bordel.

Darkness settled down on the fugitives, a darkness so intense that they stumbled over the roads, groping their way along the ditches, guiding themselves by feeling the objects on the way side. The lightning, the thick darkness, the roaring noises, and the falling ash, dismayed the stoutest hearts, and many were weeping and lamenting loudly as they hurried through the night. Some lost their children in the gloom, others fell into ditches or over the banks on to the sea-shore.

When they reached Rosebank, the light was beginning slowly to improve and many took refuge with friends there. About 10 o'clock the sky cleared, the moon appeared again, the noises ceased, and the eruption was at an end. The earthquakes noticed during this eruption were few and insignificant and the fall of ash in Chateaubelair was very slight and consisted mostly of very fine dust or sand.

In Georgetown also the day had been exceedingly fine and no warning was given of the coming outburst. When the steam- cloud rose with loud noises from the mountain a general exodus took place, but later in the night, when the darkness lifted, many returned. The ash which fell was in the form of fine dust, and amounted only to a very thin film, most readily seen on roofs and leaves and the stone pavements around the houses.

In Kingstown the consternation was intense. Some rushed about the streets in terror. Others fell on their knees and prayed aloud, but many shut themselves in their houses, dreading an incursion of the great black cloud. A small quantity of very fine dust fell in the town, but there was no deep darkness. It was noticed in Chateaubelair and Georgetown that many of the children complained of a painful feeling in their ears. This phenomenon was already described in connection with the first eruption.

The Rains

For nearly two weeks the weather had been on the whole remarkably dry, and although showers had fallen on several days, they had been light and local.

A general and considerable fall of rain was urgently needed, and it was not long in coming. On the afternoon following the second eruption, a sharp shower fell on the north end of the island, and the Soufriere smoked all over its surface as the water came in contact with the hot sand. Four days later rain fell in torrents. Total of nearly 8 inches in three days.

In the south end of St. Vincent these heavy rains did nothing but good. The parched and dust-laden vegetation was cleaned, refreshed and invigorated. The more tender plants had lost their buds and young foliage, while the stout leaves of many of the trees had been perforated or torn, or in some cases, even stripped from the branches by the rain of stones. The woods and fields rapidly resumed their green aspect, and the beneficial effect of the rains was great and immediate. But in the north end of the island, where the fields lay buried beneath a layer of sand and ashes, the results were almost disastrous.

In many places the ash was washed almost completely off the steeper slopes, even where it had been a foot or more in thickness. Mud avalanches took place on a small scale wherever the gradient was sufficiently steep to allow the moist semi-fluid material to move by its own weight. Behind the plain on which Georgetown stands, (Chester Cottage) there is a stretch of rising ground which overlooks the fields of the Grand Sable estate in bluffs a couple of hundred feet high or less. Currents of mud flowed down upon the arrowroot fields which lie below, and covered them with fans of debris. They even swept across the public road into that part of the village which is known as Browne's Town, overturning several small houses and burying their occupants in the ruin of their huts. In this way two people were killed.

Some days elapsed before water was seen to flow past Rabacca. It was hot and on more than one occasion it came down in floods of boiling mud.

From the time of the rains onward this river has been seen smoking all along its upper part, though it is only for brief periods after heavy showers that the water reaches the sea and it is then always black, turbid, and very hot. At the wharf, at Rabacca, where the sugar was formerly loaded into boats, it is said that the water is now shallower by about 12 feet. Nevertheless the old rum store stands at the same altitude above the sea level as it did formerly. The breadth of the sand beach was at most about 200 feet, but all the way from Sandy Bay to Colonarie it was evident that much black volcanic sand had recently gathered on the beaches, and that the sea-Waves were only slowly distributing it along the shore.

On the windward side of the island, ash deposits were first noticed in the fields about Colonarie, where they had been 2 or 3 inches thick, and after passing Black Point abundant remains of the ejecta of the volcano was everywhere on roadsides, arrowroot fields and on the steeper ground inland. Stones over a foot in diameter had fallen in Georgetown. In the churches and houses nearly all the windows were broken, there was hardly a whole pane of glass in the village. The damage had been greatest in the windows facing the sea and not in those looking to north, south, or to west, but the windows looking towards the volcano had also suffered, though in a less degree.

The crops in the gardens were buried, but in the fields behind the town the rains had washed away more of the material and the arrowroot was reappearing in patches. In the south end of the town and around Grand Sable House, torrents of thick brownish mud had flowed over the fields and roads from the slopes behind. A few houses were set on fire, others had collapsed under the weight of the ash which gathered on the roofs, while several had been knocked down by streams of mud on the day of the heavy rains. Over the whole of this country the rains had caused immense erosion, and everywhere the surface was sculptured with furrows and runnels.

The Cause of the Deaths

Owing to the urgency of the case, it was impossible to perform autopsies on the bodies of the dead in St. Vincent, and however much we may regret this from a scientific point of view, we must recognise that the first call on the energies of the medical men was to attend to the wounded and give them what assistance they could. At first the number of doctors in the island was too small to enable them to cope with the sudden emergency, but help was rapidly provided from the adjacent British islands and the final results were brilliant, It was several days before the state of the volcano warranted the exploration of the devastated country on an extensive scale and when the bodies were finally all discovered and interred, they were very often in a condition which left little hope of obtaining any important information by means of postmortem examinations.

Fortunately, the evidence as to the lethal agencies at work is fairly clear and conclusive and the opinions formed by the doctors who had care of the survivors are entirely in accordance with the geological facts regarding the nature of the catastrophe. From Dr. C. W. Branch, Dr. Dunbar Hughes, and Dr. Austin, of St. Vincent, and from Major Wills, R.A.M.C, and Dr. Hutson, of Barbados, we obtained most of the information on which we have based our conclusions.

We had also an opportunity of examining many survivors who had passed the afternoon and night of May 7th in the Carib Country. Some of these had completely recovered, others were in the hospital in Kingstown, many were very unwilling to retail the horrors of that afternoon when their friends, relatives, and families had perished at their side.

Without doubt steam laden with hot dust was the principal cause of the fatalities. When the hot wave struck the houses all the occupants felt a sudden pain in their mouths and throats. This was principally due to the fine hot dust, which was intensely irritant. After a minute or so there was the feeling of pain in nose, mouth, and throat, and on the exposed parts of the body, many who survived complained that they also felt a burning sensation in their breasts and abdomens the result probably of their having inhaled the hot dust into their bronchi or swallowed it and thus scorched their throats, or perhaps also their stomachs.

The sufferers gasped and cried for breath, but soon their cries were stilled by the approach of asphyxiation. They felt as if someone was powerfully compressing their throats, and at the same time their thirst was excessive.

The duration of the fatal wave of hot gases and dust was certainly brief, probably not more than three minutes, but it seems clear that death was not instantaneous, or at any rate on the estates in the lower part of the Carib Country. At the same time it must be remarked that apparently after a minute or two the conditions had a lethal effect on the great majority of those subjected to them. The cries were succeeded by silence and inarticulate groans and death followed almost at once. We were told that in some of the houses where the dead were heaped upon the floor, as in Sutherland's shop in Overland Village, where 87 perished in a little room, the bodies lay regularly piled on one another the whole mass, living and dead, had fallen at once.

Only those survived who had shut themselves up in cellars and rooms with tightly- closed windows. We have already given some instances which prove how important it was to avoid direct contact with the cloud. In the cellar at Orange Hill 40 survived, but 30 who were in the passage leading into it died. In Turema all who had escaped had taken refuge in tightly shut-up rooms. At Rabacca many were saved in the same way. All human beings and animals which were in the open air perished. In some cases one or two occupants of a house were spared, while all the others died.

In Overland Village, and a few other places, the first ash brought in the blast was wet and stuck to the walls of the houses. This was the case also in Fancy. This wet mud occasioned severe burns, as it adhered to the naked skin, and many of the sufferers had extensive burns, from which the skin was peeling. But in most cases the dust was dry and clung principally to those parts which were moist, like the lips, or were covered with short hairs, like the backs of the forearms.

Many of the injured lay among the dead bodies on the floor, covered with a thin film of ashes, groaning, with parched throats, unable to raise themselves and search for water, waiting for death. Most of these died within an hour or two, others dragged on for a couple of days one case was taken to hospital and died three days after the eruption. The direct cause of death was shock and exhaustion.

Others were removed and died under treatment, partly from the shock of their burns and the terrible experiences through which they had passed, partly from the other secondary effects of their injuries. Fortunately, they were comparatively few, only 70 deaths from burns and other causes occurred in the hospitals.

After thought

Several lessons should be learned from this graphic account that should make us better prepared, "God forbid" anything like this was to ever happen again. It is clear that the people living on the Leeward side have a much better view of the volcano as it appears to be less obtrusive by clouds and would therefore be better equipped for an early evacuation. Click here to see the leeward view. Residence on the Windward side can not readily see the volcano when it is cloudy, although today it can be clearly seen on most days.

It would appear that the blast form the volcano carrying dust and sulphur was the main cause of deaths, and those exposed to it stood no chance, so other than fleeing, locking up indoors seems to be a safe course of action. Houses are more substantially built now a days so better security should be available. We now have the safety valve of a bridge over the Rabacca river, but this needs to be regularly checked and maintained to ensure good stability. Finally, earthquakes and thunder appears to be a sign that danger is imminent, unfortunately it took well over Twelve months before this was realised in 1902.

One would like to think that more advanced monitoring systems are in place now a days so hopefully if the volcano does erupt again the loss of lives will be miminimal.

Disclaimer

Many of the photographs used in this page were obtained by research and does not belong to me. Credit will be given to known owners below.

Tempest Anderson, Steve Parks,Tadashi Tsukamoto.