Copyright/Disclaimer Notice

Please note that all text, images, graphics and photographs that are my intellectual property, are copyrighted. Where the items have not originated from myself every attempt has been made to credit the original author/creator. If you think there is an image or item that has not been correctly credited please contact me so I can make the appropriate corrections.

In all cases I will ask, at minimum that credit (and a link) be given to www.georgetownsvgrevisited.co.uk and all copyright banners on images remain intact.

European Invasion on St Vincent

Many of you would already know the stories of Columbus, Francis Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh and all the other conquerors that they told us about in school, so I won't elaborate too much on the so called European discovery of St Vincent. Instead I want to focus on some of the things that they didn't tell us about.

The Europeans were not the original residents of St Vincent. They, (as we would say today) gate crashed it and caused havoc among the natives living here at the time and also on future generations to come. From its first moment of settlement, St. Vincent was a point of contention between the Caribs, France and Britain.

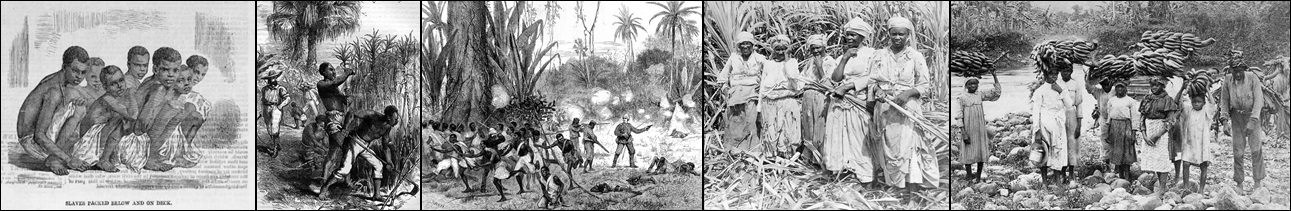

After many unsuccessful attempts to conquer the natives, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle negotiated between Britain and France was signed in 1748. Among the provisions of the treaty was one confirming the neutral status of St. Vincent. European nations were to be withdrawn from the islands, leaving it in the possession of the Caribs. The French settlers on St. Vincent, remained on the island, but peace between the two European powers would not last very long.

A Seven Year War between France and Britain (1756 to 1763) gave Britain ownership to St.Vincent once again. This saw the displacement of the French planters on the island by British regional elites from surrounding Caribbean islands. French land-owners who were willing to stay in the anglicized

island had to re-buy their properties. The English gave the island a Governor, Council, Assembly, and Justice Court.

Before Great Britain obtained control of St. Vincent, French priests and, later on, a few French planters were known to have landed along the Leeward (or western) coast, thus beginning the first recorded European settlements. These hardy individuals came from Martinique and Guadeloupe with the aim of escaping the conventions of metropolitan rule. Ever since then there has been numerous battles between the French and the British to gain possession of St. Vincent.

Why was St.Vincent so appealing to these people? After all, there was no gold or diamonds in the mountains. Well there was gold of another kind, to be manufactured, White Gold (Sugar). Sugar was in great demand though out Europe and huge profits were to made by large estate owners. The soil of St. Vincent’s had been for some time known to be the richest and most fertile of the Caribbean islands, and the area which the Caribs possessed to be the most fertile of St. Vincent.

Encouraged by this and by lucrative sugar profits at home, the new British planters aimed at nothing less than Possession of the whole Territory of the Island. They wanted the island to settle and develop as a sugar island. Not content with the acquisition of 20,000 acres of fertile land taken from the Caribs by a treaty forced upon them in 1769, the new settlers continued to expand into Carib territory.

From the beginning, French authorities had stressed the importance of maintaining good relations with the Caribs in St. Vincent whenever possible. After the Treaty, when St. Vincent was in English hands, the France-Carib relationship allowed France to indirectly carry out a guerilla war against her colonial rival in an attempt to regain control of the lost colony. English colonial policy makers, on the other hand, were much more concerned with the suppression of any potential Carib military force, and the seizure of Carib lands in order to maximize agricultural profits, than they were with fostering Carib allies.

From the beginning, French authorities had stressed the importance of maintaining good relations with the Caribs in St. Vincent whenever possible. After the Treaty, when St. Vincent was in English hands, the France-Carib relationship allowed France to indirectly carry out a guerilla war against her colonial rival in an attempt to regain control of the lost colony. English colonial policy makers, on the other hand, were much more concerned with the suppression of any potential Carib military force, and the seizure of Carib lands in order to maximize agricultural profits, than they were with fostering Carib allies.

Their plantations, which at first were not much larger than their French predecessors, began to expand rapidly increasing profits with the acquisitionof fertile Carib lands. This initial period of English rule saw the rise of sugar, production in St. Vincent increased 74-fold from 1766 to 1775. St Vincent exported 3,129 tons of sugar in 1774, more than any of the other British colonies annexed by the Treaty of Paris save Grenada. British Vincentian sugar production was just beginning, and would increase 300 percent by the end of the century. With such profits to be had the French started another war and gained possession of the island once again in1779, Seventeen years after being under British rule. This occupation only lasted for four years. In 1783, St Vincent was back in the hands of the British. Can you imagine the confusion in the minds of our fore parents with all these changes?

.

"The Breadfruit was introduced in St Vincent from Tahiti, in 1793 as new food source for the slaves.

The British and the French were at it again in 1793. War was declared by the French. A war that was to last for 23 years. French agents, along with sympathetic French Vincentian planters, pursueded the Anglophobic Caribs to make war against the British. Arms and ammunition were sent from Guadaloupe, and it was planned to attack Kingstown on the night of 10 March 1795 by two forces led by Black Carib chieftains Chatoyér and Duvallé.

The Second Carib War, waged with the support of French troops and supplies, continued for four sanguinary years, with both sides frequently gaining, then losing the upper hand. For the first 15 months of the conflict the English would be periodically forced into a southern enclave around Kingstown, and the Carib and French into the northern parts of the island. The Carib leader Chatoyér was allegedly killed in single combat with Major Alexander Leith on 14 March 1795.

The End of French and Caribs Resistance on St Vincent

After the English recaptured St. Lucia (which had been providing supplies and reinforcements to the Franco-Carib fighters), the victorious redcoats were brought in to deal with the situation on St. Vincent. On 10th June 1796 The French troops surrendered outright, and were released on parole and eventually transported to their own island colonies. The Caribs, however did not surrender, but fought on. Over the next Three years, the British would push on relentlessly, burning over one thousand native houses and any canoes they came across, in a genocidal effort to purge the island once and for all of the Caribs.

In 1797,the assault on the Caribs was led by Ralph Abercromby. Thousands of the Garifuna were slaughtered, no Christian or human mercy was shown. It was violence in its natural state against innocent, defenceless people. Many Garifuna who sought to escape by way of the sea, without boats, went solemnly and heroically to their watery grave.

In 1797,the assault on the Caribs was led by Ralph Abercromby. Thousands of the Garifuna were slaughtered, no Christian or human mercy was shown. It was violence in its natural state against innocent, defenceless people. Many Garifuna who sought to escape by way of the sea, without boats, went solemnly and heroically to their watery grave.

Having massacred thousands of the Garifuna, the British then rounded up some five thousand of the Garifuna and corralled them on the off-shore island Balliceaux. Devoid of food and fresh water, after a few months an estimated two thousand or so died. The rest were transported forcibly, to Roatan Island off British Honduras, now Belize. Historians tell us that the only animals which survived on Roatan Island were lizards and iguanas. But the Garifuna survived and thrived.

Different People

As a boy growing up in the 1960s most of the population in my neighbourhood were Black. There were also a few Indians several red skin people and not many whites. The few red skin people that I can recall were Miss Ivy, Peter Tisherria and Rex Frasier who lived in Mt Bentinck.

Miss Ivy was a shop keeper, Peter had land in the mountain and was farming almost every day. He could be seen most evenings on his donkey laden with feeding and provision coming home after a hard days work.

Peter didn't mix much with the locals, he was a quiet man. He however had a son with a local lady. The son and I grew up together in Back Street. His correct name was Gerald, but we use to call him Madera, not knowing at the time why.

Most of the Indians as I recall did not mix socially with us out side of school. While we were out doors playing ball they were probably with their books. Their parents were mostly shop keepers or land owners. Strangely, they didn't have traditional Indian surnames. There were Baileys, Huggins, Goodridges, Da Silavas, Sutherlands, Crichtons and Hadleys

The Whites in the neighbourhood were the Crozers and Child. The Crozers owned businesses and lands. Sony Child probably controlled most of the lands in Georgetown. He lived in a mansion far away from other people. We didn't question the reasons behind the different races when we were kids, to us it was what it was.

Where did all these different races come from?

After the dispossession of the Carib's territory many high ranking British were allocated vast amount of lands. A hero of the late Seven Years' War, General Robert Monckton who captured St. Vincent and Martinique, was given 4,000 acres on the south Windward coast between what is today Biabou Village on the north and Stubbs Village on the south, extending inland to the head waters of the rivers flowing down the Mesopotamia Valley. Monckton never settled his land but sold it instead for £30,000.

An American Royalist from Georgia, Colonel Thomas Browne, was granted 6,000 acres stretching from Byera River in the south to Cayo River in the north, including the area of seven large, recently established estates, namely Tourama, Orange Hill, Waterloo, Lot 14, Rabacca, Langley Park, and Mt. Bentinck. The land was awarded to him by his friend and Governor at the time Charles Brisbane. The local planters protested and it was later proved that this huge amount of prime land was acquired though false documentation. Browne was tried and found guilty and imprisoned. However he was allowed to keep Grand Sable Estate, 1,600 acres, the largest single estate in St.Vincent.on which he finally lived until his death at Grand Sable Plantation, in 1825.

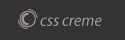

As previously stated, the island was settled and developed purely as a "sugar island and labour requirements for sugar estates were met by African slaves. On August 1834, all slaves in the British Empire were emancipated, but still indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system. The apprenticeship system was a system implied to force the ex-slaves to return to the plantation. They were to give 40 and a half hours free labour and any time after that they were to be paid for their work. To maintain sufficient workers in the fields at low cost after Emancipation, laws were passed permitting foreign labourers to enter under paid contracts.

Let's just pause here for a minute. They were prepared to ship in foreign labour at a cost and pay them to work? Why not pay the free slaves instead?

Arawak Indians Yellow Caribs Africans Black Caribs Portuguese Indians

In 1845, the first shipload of immigrant labourers, 254 Portuguese Madeirans, arrived in the island to begin their Indentured service period. The bulk of the Madeiran immigration to St. Vincent occurred between 1846 and 1850, when 1,848 immigrants debarked in Kingstown, making a total of 2,102 indentees, including the arrival of the first group in 1845. Although they were cultivators in Madeira, many of the immigrants who remained after the expiration of their service contracts left the fields to embark on commercial ventures as shopkeepers. These factors forced the colonial Government to seek an alternate source of indentured workers. Certain areas of the Indian subcontinent (Calcutta) with people to spare were willing, efficient tillers of land eager to be indentured overseas. Preparation for the importation of East Indian indentured labourers into St. Vincent did not, however, begin until 1857.

Indentured East Indians In St Vincent 1861

From 1834 to 1844, and again from 1848 to 1851, the Governor - General of India stopped emigration to the British West Indies because of mistreatment of the East Indians on the estates and irregularities in recruiting practices within India. In view of this as the supply of liberated Africans declined, St. Vincent had to enact laws which would satisfy the Indian Government before immigration of the East Indians could begin. Accordingly, several acts were passed in 1857, great care being given to formulating terms and conditions of contract service for the "Coolies."

Indian labourers were first recruited to St Vincent, because planters found the Africans and Maderians unsatisfactory. The terms of the Indian indenture differed greatly from those of the Africans and Maderians. The length of service was initially Five years and Indians had to remain on the estate as industrial residents for this period. Furthermore they could not travel off their estate without permission and even when their indenture was over they could not legally move to any of the other island in the Caribbean. Those that agreed to remain as indentured labourers for a further Three years were entitled to a return passage to India or a cash payment, they were also to receive free housing, medical attendance and wages of Ten cents per day.

The planters wanted the "Coolies" attached as long as possible within the legal indenture term of Eight years to estate agriculture, therefore Inducements were given for the indentees to serve out their terms in the estate fields, rather than have them pay a commutation fee to exclude themselves from the final Three year commitment. To prevent the disillusionment of Coolies assigned to poorly run estates, each lndentee could change his estate after the first Five years of service. It was only after the initial 5 year term on an estate that an lndentee had the option either to remain in field agriculture or to pay for the release of his last 3 years, thus freeing himself from all further contract obligations.

Maderian indentured adult labourers were expected to work for Three years and received wages, housing and provision grounds.

In 1874, the terms of indenture altered and Indians had to remain as Industrial residence for five years on their estates and could receive a free passage home if they completed a further Five years labour on their estates. In an attempt to dissuade many labourers from leaving St Vincent or settling in Towns, labourers were given a bounty of Ten pounds in addition to a free return passage if they agreed to sign up for a second Five year term

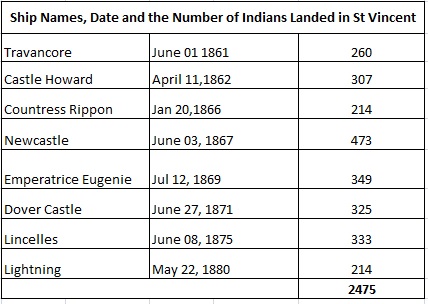

The first shipload of "Coolies" arrived in St. Vincent in 1861, bringing 260 East Indians from the port of Madras; there were Eight additional shiploads between 1861 and 1880, all originating from Calcutta. The total number of Indians landed in the colony was 2,429 men, women, and children. Most of the "Coolies" were requested by and assigned to the larger sugar estates along the Windward coast, including many of the Carib Country estates. Many of these Indians were hoping to save enough money to buy land, once their indentures were completed and to work as casual labour on estates much as the native Vincentian population had been doing since the end of slavery.

Between 1874 and 1878, the average annual number of indentured "Coolies" remaining on Vincentian sugar estates was 1,454. After 1880, no more "Coolies" were imported into St. Vincent, because the Government was unable to provide sufficient funds for such labour, and in any event, the disastrous decline in sugar prices in 1882 affected the income of the planters so severely that the scheme became redundant, driving many estates into debt and bankruptcy.

In all there were eight shiploads of Indians to St. Vincent over a period of 20 years between 1861 and 1880, the first and only one originating from Madras, while the other seven ships left from Calcutta bringing a total of 2,475 Indians. On the other hand most of the 2,100 Portuguese arrived over a three-year period between 1845 and 1848. Most Indians were Hindus from the Northwestern Provinces, Bihar and Oude.

Conditions on the estates were harsh for all indentured labourers, many died within their first year. Many of those who died suffered from bowel complaints, Yaws and worms others were covered in ulcers that did not heal. Managers complained that Indians performed less than Two Thirds of the daily task performed by Creoles, as a result planters decided to reduce their wages and set their own level of pay which was at the time deemed illegal. However, it was also true that many of the indentured labourers were too weak to cope with the work load expected of them. Indians initially worked separately from Creoles labourers but were eventually encourages to work side by side.

Indians complained that they had been unfairly deceived about the condition in St Vincent before they left India. Wages in St Vincent were considerably lower than in other Islands but they had limited means of appealing against cruelties and abuse. In all reports and documents, Indians were universally referred to as "Coolies" an expression that instantly distanced them from other labourers as well as been seen as poor workers, they were also accused of being dishonest and complaining. All the men making these statements were aware that Indians were systematically been cheated out of their promised wages by planters.

In 1849 when the first group of Madeirans had completed their contracts many started to look for better conditions. Some travelled to other islands or moved to the Towns and began trading. In 1861 less than half of Madeiran immigrants remained in St Vincent. Over 100 moved to Kingstown.

At the end of their first period of indenture many Indians chose to leave their estates and move closer to Kingstown. They settled mainly at Calder, Akers, Argyle, Richland Park, Park Hill, Georgetown and Rose Bank others applied for passports and moved to Trinidad and British Guiana for higher wages, and more access to land and become part of the Indian community there. In response to this an act was passed in 1879 prohibiting ship captains from transporting any Indians from St Vincent.

Many Indians found employment in St Vincent scarce and in 1885, Five hundred and Fifty Four free Indians were repatriated because they had been refused work on the estates. In all, over 45% cent of Indians who came to St Vincent returned home. In 1902 the Indian population in SVG was just under 500 but by the 1950s Indians in SVG numbered over 5000. It was not uncommon for a married couple to have more than ten children.

A full unbiased account of life on the plantation estates in St Vincent between 1834 and 1884 can be found on this link. Please click Colour, Class and Gender in Post Emancipation St Vincent